The AP reported yesterday that “opponents of Amendment 1 are asking a federal judge to void the vote that amended the Tennessee Constitution to make it easier for lawmakers to restrict abortions.” (For a refresher on Amendment One, see here.)

The complaint was filed yesterday afternoon in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee (Nashville). The plaintiffs are eight residents of Middle Tennessee—professors at Vanderbilt, medical professionals, government workers, and a reverend among them—who voted “no” last Tuesday. The voter-plaintiffs allege that the method by which state officials chose to tabulate the votes on November 4 violated their constitutional rights to Due Process and to Equal Protection under the law, and they are asking the court to invalidate the results of the referendum on Amendment One.

How did state officials tabulate votes?

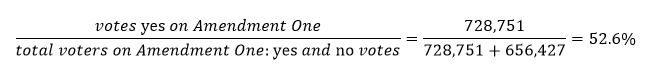

A lot of people assumed on Tuesday night that passage would hinge on a simple majority vote—whichever side had the most votes would win. Coverage of the election results in Tennessee last week almost exclusively focused on the votes “for” and “against” Amendment One (728,751 to 656,427), with most media outlets declaring passage by “53%.” (Here’s HuffPo, The Tennessean, and NPR saying the same. Even the Secretary of State may have been confused, since these were the only numbers published at elections.tn.gov under Amendment One.)

However, Tennessee is only one of a handful of states that requires a “double-majority” on a Constitutional Amendment: a measure must pass by a majority on the issue as well as by some other measure of majority. In Tennessee, that second measure is “a majority of all of the citizens of the state voting for governor.”

Any amendment or amendments to this Constitution may be proposed in the Senate or House of Representatives, and . . . [submitted] to the people at the next general election in which a governor is to be chosen. And if the people shall approve and ratify such amendment or amendments by a majority of all the citizens of the state voting for governor, voting in their favor, such amendment or amendments shall become a part of this Constitution.

Article XI, Section 3 of the Tennessee Constitution

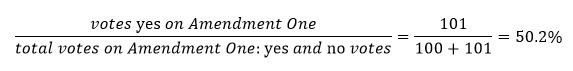

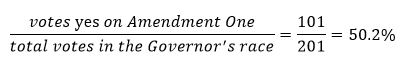

Illustration:

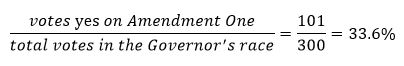

First criterion: If 100 voters cast a ballot against Amendment One, and 101 voters cast a ballot for Amendment One, then there is a majority on the issue.

Second criterion: If all 201 voters cast a ballot in the governor’s race, 101 voters casting ballots for Amendment One is enough for passage because it also constitutes a majority of voters for governor.

However, if 300 people cast ballots in the governor’s race (meaning that some people must not have voted on Amendment One):

The initiative would not pass. It would not meet the second criteria for constitutional amendment—that the number of “yes” votes must also be a majority of the number of voters who cast ballots in the Governor’s race.

Comment: One can see how a system like this might be beneficial in keeping interest groups from passing legislation that no one else knows about. For instance, if only one person voted yes on a Constitutional Amendment, because perhaps no one else knew anything about it, some would say it should not pass. It would be helpful in that case to use the total number of votes in the Governor’s race (or some other number) to assess the fairness of the vote.

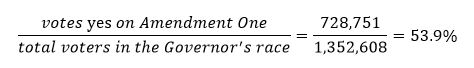

The number of voters in the governor’s race was 1,352,608. This means that on the first criterion:

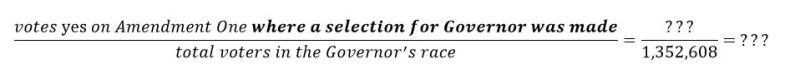

And on the second criterion:

So, it still wins. What’s the big deal?

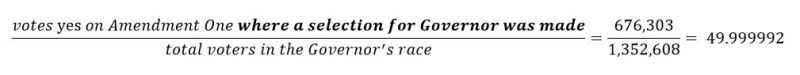

The complaint that was just filed argues that the way the second criterion was calculated (above) is incorrect. The plaintiff-voters contend that the language of the Constitution (“a majority of all of the citizens of the state voting for governor”) should be read to mean that only the ballots which made a selection for both governor and Amendment One should be counted. In other words:

. . . is the proper formulation of the second criterion.

Information regarding the number of ballots submitted with a “yes” vote on Amendment One that also made a selection for Governor is not available (as I mentioned before, not even the total number of votes in the Governor’s race was featured on the Secretary of State’s website), and so it is impossible to tell what the “actual” outcome should have been, according to the plaintiffs. They’re asking the judge to stop the State from certifying the results until they are tabulated in this way. If it’s not possible to go back and count, they want the results invalidated.

It is reasonable to assume that the number of “yes” ballots on which a selection for governor was made is much lower (for reasons discussed below). And, under the plaintiffs’ formulation, if less than 676,304 ballots cast a vote for both Governor and for Amendment One, then the Amendment would not pass.

Effectively, if it were revealed that 52,448 of the 728,751 “Yes” voters abstained from voting in the governor’s race, Amendment One should not pass.

Why do the plaintiffs think that’s the way votes should be tabulated?

The plaintiffs say that the wording of the Tennessee Constitution demands their formulation. (Stay tuned—I’m hoping to do some research on what the Tennessee Legislature actually intended by these words in the next few weeks or so.)

They are also arguing that to read it in the way that the State is reading it violates their rights to Due Process and Equal Protection.

Due Process Claim

The plaintiffs rely on League of Women Voters v. Brunner which states that “The Due Process clause is implicated . . . in the exceptional case where a state’s voting system is fundamentally unfair.” Because the State has ignored the dictates of the Tennessee Constitution and instead implemented an arbitrary new standard, the argument goes, the system by which the votes were tabulated is “fundamentally unfair.” A violation of the Due Process rights of these (and all) voters requires strict scrutiny review, and the plaintiffs argue that the State will be unable to show any compelling reason to limit the right to a fair voting system.

Equal Protection Claim

The plaintiffs rely on Reynolds v. Sims which states that “The right of suffrage can be denied by a debasement or dilution of the weight of a citizen’s vote just as effectively as by wholly prohibiting the free exercise of the franchise.” In other words, a system that counts some votes less than others is just as bad as one that blocks the door to the polling station.

As the complaint points out, Tennesseeans who voted “no” on Amendment One last week (and also made a selection in the Governor’s race as they say is required) were “subject[ed] . . . to a coordinated scheme.” It appears that some politicians and organizers in Tennessee—aware of the way in which the State intended to tabulate the votes—encouraged voters to abstain from “the uncontested governor’s race” in order to “double their vote” (p. 4). Here’s a photo of the mailer that my family in Rutherford County received:

Rick Womick wasn’t alone. The complaint cites a YouTube video, the truthon1.org website, and a church bulletin that all offered similar advice.

Because this way of counting votes effectively makes some ballots more important than others, the argument goes, the Equal Protection of these (and all) voters was denied.

Unqualified legal opinions from a non-lawyer

I’m not sure that the argument that the “plain language” of the Tennessee Constitution dictates counting the votes in the way that the plaintiffs outline is very convincing to me. For one thing, voters, news agencies, and even State officials collectively “misunderstood” it, making the language, at the very least, not “plain.” The argument of the plaintiffs raises a valid question, though, about what the language means that will probably need to be decided by a judge.

It’s hard to imagine that the legislature, in crafting this constitutional language, meant to say that only those voters who cared enough to vote for Governor were qualified to vote on various constitutional amendments. Rather, as I mentioned in the comment above, it seems to me that the total votes in the Governor’s race was just the benchmark agreed-upon so that the legislature could be reasonably sure an Amendment was not only passing because of a motivated minority group. It seems to me like this purpose could be effectively achieved by reading the Tennessee Constitution in the way that the State proposes. I’ll be looking into legislative intent regarding Article XI, Section 3, and hopefully I will be able to publish a Part II here shortly.

I think that the argument regarding Equal Protection though is very persuasive. In fact, I think that the plaintiffs could argue that their rights were denied even if a Court found that the State’s method of tabulating the votes was in keeping with the Tennessee Constitution. Even if it was “proper” to count all of the votes in the Governor’s race, we are still left with a system that, if it cannot be characterized as “fundamentally unfair,” almost definitely gives more weight to some votes than to others. Even if the Tennessee Constitution says to tabulate the votes in this way, a ruling by the United States Supreme Court (like that in Reynolds, see above) would trump any state constitutional provision.

I think.

As always, my disclaimer is that I’m not a lawyer (though I am six weeks closer to being one than I was in my last post!). I offer my thoughts here mostly as a digest for friends and family who may not have the time or resources to dig up the complaint or the Tennessee Constitution, and to encourage discussion. If you think I’ve made a mistake somewhere, please leave a comment so that I may make necessary corrections.

And don’t take my word for it. By registering for a PACER account, anyone can search for and read the complaint themselves (it’s free if you search for less than $15 worth of information in a three-month period, though beware of racking up a bill through messy searches). To aid in your search: the complaint in “George, et al v. Haslam, et al” was filed in the Middle District of Tennessee on November 7, 2014.

Thanks for reading!

- abortion

- abortion rights

- Amendment One

- Civil Rights

- Constitutional Amendment

- Due Process

- election law

- Equal Protection

- Federal District Court

- George

- Haslam

- law

- lawsuit

- legal

- majority

- Middle District

- Middle District of Tennessee

- November 7

- pro-choice

- pro-life

- reproductive justice

- Reproductive rights

- State of Tennessee

- tabulation

- Tennessee

- Tennessee Constitution

- TN

- Vote No on One

- Vote Yes on One

- voter referendum

Thanks for the research here sweetie! I’ve been up to my ears in Bar Review, but I took a break on election night to watch the carnage.

I hope you’re loving school, and Chicago, and your new friends!

Going to see A and G in Vegas this weekend – love from all of us!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You know it! Law school’s been pretty fun (and kind of helpful!) so far. I’m not sure how much I’ll be posting about the intimate details (as my school chums might see! :3) but I cannot wait to catch you up. I think I’m going to see Jenny over Thanksgiving–want to make it a threesome?

LikeLike

Thanks for this post! Very helpful.

LikeLike

It’s my pleasure. I’ll continue to post as things develop.

LikeLike

Is there (or shouldn’t there be) a law against outright deceit for votes on a non-partisan referendum such as the Amendment 2. The (only) TV ad that continuously ran said: “yes meant we would continue to vote and select our judges”. As you know (but so many people probably do not) we have not voted for nor selected our judges since 1971. Wouldn’t this also be “fundamentally unfair” by “weighting the vote” since this blatant deception was made by a government authority we are supposed to trust? Being our own Governor Haslam !

LikeLike

Finally, a ray of hope at the end of a very depressing week. Thanks for researching and posting. I’ll look forward to the updates. Good luck in your last few weeks of school!

LikeLike

Of course. I’m happy to do it. Here’s to more good news, and thanks for reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

If this suit is successful, it could certainly raise a lot of questions regarding other legislatively-referred constitutional amendments, at least on this last ticket. It’s an interesting consequence/complication (but one that I hope will not eventually impede the progress of this particular action).

I’m afraid I didn’t understand as much about Amendment 2 as I like to think I did about Amendment 1, but I’m not sure I even could have. It was sold in a really peculiar way, and I could barely hear arguments against it over the overwhelming support from the Tennessee Bar, various other legal organizations, and even elected officials and judges themselves!

Truth in political advertising gets so tricky, I think, because soundbites can almost never be 100% accurate.

LikeLike